Prospects for high-yield bonds

How inflation and economic indicators are affecting one area of fixed income

High-yield bonds used to be considered the riskier end of the fixed income sector, but they have become more established in recent years due the relentless search for income in a low interest rate environment.

But as economic sentiment worsens, doubts emerge about some of these assets, not least because in a loose monetary environment many companies of questionable quality may have sold debt to finance themselves.

Bond managers of all complexions are looking at how to grapple with changing economic circumstances, and what a high inflation and low growth environment means.

In these articles we explore some of these issues.

Advisers see role for high-yield bonds

Advisers see high-yield bonds as part of the solution for income investors in the current climate, according to the latest FTAdviser Despatches poll.

The poll found that more than 90 per cent of respondents see a role for high-yield bonds.

It is an asset class that has marginally underperformed against strategic bond funds this year to date, but which may look more attractive as a result of higher inflation.

There is a growing need for portfolios to generate higher levels of income to help clients in decumulation mitigate the higher cost of living.

High-yield bonds are those with a credit rating of below BBB, while those above that rating are known as investment-grade bonds. The highest credit rating a high-yield bond can achieve is BB.

Respondents to our poll, which was conducted via ftadviser.com, were overwhelmingly in favour of deploying some capital to the asset class, despite its sensitivity to the performance of the wider economy and correlation with equities.

The poll found that 96 per cent of respondents favoured high-yield bond funds right now, with only 4 per cent not seeing a role for such products in the present climate.

david.thorpe@ft.com

What is the outlook for the high-yield bond market?

In many ways, the factors that are driving the outlook for the UK economy as a whole are also acutely important for the performance of the high-yield bond market.

For high-yield bonds to thrive, economic conditions tend to need to involve high and rising inflation, and a positive economic growth outlook.

The former is important as it increases the relative attractiveness of the income from the bond, when compared with cash or government bonds, which are traditionally viewed as lower risk, but which offer lower yields as a consequence.

The latter is important as economic growth would be expected to increase the likelihood that the companies that borrow the money will be able to pay the interest and coupon on the debt.

Thus it could be said the ideal conditions for high yield to thrive actually occurred in 2021 and in the opening months of 2022, as investors adjusted their expectations for how high inflation could go, but also were generally optimistic around the outlook for GDP growth.

As 2022 rumbles on, the inflation part of the narrative has come through, but growth expectations globally have been revised downwards.

We knew from the signals being sent by central banks that 2022 would see a change of market conditions

The Bank of England has, in its latest forecasts, anticipated a sharp deceleration in the level and pace of economic growth in the UK over the coming 12 months, while at the same time predicting that inflation could peak at more than 10 per cent this year.

The challenge facing investors is that the former outcome would typically encourage investors to buy lower risk assets such as government bonds, but the value of the income from those is severely challenged by higher inflation.

Those who buy the high-yield assets as a mitigant against inflation face the challenge that recession could lead to more companies defaulting on their debt, and investors in that debt losing money.

Colm D’Rosario, co-head of emerging market and high-yield corporate debt at Amundi, says: "At the start of the year, I think most people were quite constructive in terms of their outlook for the global economy, and expected growth to continue and rate rises to happen.

"But the Ukraine war and the lockdowns in China have changed that; policymakers are now having to walk a tightrope, trying to combat inflation without completely killing off growth."

But he says that while the macro outlook is not, on the surface, positive for high-yield bonds, there are circumstances which may mean the picture is less onerous for investors in the asset class than first appears to be the case.

He says the pandemic caused companies to reduce debt levels, while the positive economic growth conditions of 2021 meant corporate earnings were strong, enabling businesses to build up cash balances in advance of any economic storm.

Yields are now starting to look very attractive, certainly at the higher quality end of the high-yield market

This is atypical of many economic cycles as recessions more frequently occur after periods of what Alan Greenspan, a former US Federal Reserve chairman, called “irrational exuberance”, as businesses respond to the period of strong economic growth by borrowing more, and leave themselves much less prepared for any subsequent downturn, as happened during the global financial crisis.

D’Rosario is not completely bullish on the outlook for his asset class though, as he says high-yield bond prices are not currently pricing in a recession, and as a recession is a possible outcome this reduces the relative attractiveness of high-yield bonds.

Rhys Davies, bond fund manager at Invesco, says he came into this year being quite cautious on the outlook for high yield because the positive economic outlook of 2021 led to the price of high-yield bonds rising sharply, but with growth always expected to slow down this year, even without the Ukraine conflict, he felt the higher prices, while they may have justified the conditions of 2021, were wrong for the likely conditions of 2022.

He adds: “In 2020 high-yield bond prices made a strong recovery and 2021 was a very stable year, but we knew from the signals being sent by central banks that 2022 would see a change of market conditions.”

But he says the slightly worse performance of the first part of this year means that prices have fallen and “yields are now starting to look very attractive, certainly at the higher quality end of the high-yield market”.

Central banks have a very difficult balancing act ahead of them

Chris Higham, a senior portfolio manager in the fixed income team at Aviva Investors, says he will remain underweight high-yield bonds relative to the rest of the market until the interest rate hikes, currently much discussed, actually happen, as he wants to see the impact of those changes on the prices of bonds before potentially increasing his investments.

He says the recently announced rate rises in the US and UK are just “the starting gun” on a rate rising cycle.

Sophie Burke-Murphy, investment director at discretionary fund manager Featherstone, says: "While high-yield bonds have historically performed quite well in a rising rate environment, we don’t see them as a particularly attractive asset class right now.

"Central banks have a very difficult balancing act ahead of them, trying to keep inflation under control by raising rates without sending global economies into recession.

"The risk of policy error is high and if global growth does slow down significantly high-yield bonds are not going to be a comfortable place to hide.”

QT or not QT?

One of the major drivers of bond market performance over the past decade has been the policy of central banks of buying bonds as part of quantitative easing, with the aim of driving bond yields down, to keep interest rates low and stimulate economic activity.

But after more than a decade of that policy, central banks are now preparing for quantitative tightening, which involves selling bonds they have bought back into the market.

In effect, central banks are moving from being buyers of bonds at almost any price to sellers of bonds at almost any price, just at the time when higher inflation may be dampening demand for bonds.

Although only a relatively small segment of the bond holdings of central banks will actually be high-yield bonds, the impact on that part of the market could be akin to the impact a stone has as it ripples through water.

So when government bonds are sold, this causes the price of those assets to fall, pushing the yield upwards.

The unwinding of QE means its harder to look at any part of the bond market in the normal way

Because the yields on lower risk bonds are rising, this makes the higher yields of the riskier bonds less attractive.

Higham says that because high-yield bonds in European markets were “a big beneficiary” of QE, it is intuitive that a reversal of that policy would lead to high-yield bonds struggling.

But Davies takes the view that the market always knew that QT was coming and has over recent years adjusted to this, meaning the impact of any future shock will be greatly diminished.

Joseph Lind, senior portfolio manager at Neuberger Berman, says the QT issue is most likely to have an impact on the “lower quality” end of high yield, which he classifies as bonds with a credit rating of CCC or below.

Jon Mawby, bond fund manager at Pictet Asset Management, says: “The unwinding of QE means it's harder to look at any part of the bond market in the normal way.

"Some of the areas of the bond market which are supposed to be safer havens have suffered this year, but investors are starting to focus on being shorter duration, which usually helps high-yield bonds."

He says volatility may stay high for an extended period, but he finds the top end of the high-yield bond market to have attractive valuations.

The highest credit rating a bond within the high yield universe can have is BB.

Quality control

There are competing theories as to the level, in aggregate, of quality of the investments on offer in the high-yield bond market right now.

One theory advocated by Davies at Invesco, among others, is that QE and low interest rates enabled many unviable companies to finance themselves in the high-yield bond market, meaning there are collectively more poor-quality bonds in the market now than historically.

The counter view, shared to some extent by Higham, is that the two years of the Covid-19 pandemic flushed out the poorest companies, and enabled the stronger to build up their credit-worthiness.

Lind describes the concept of companies that are unviable being able to survive as “zombie credit”, but says it is largely at the lower end of the high-yield market that such businesses exist, while in the market as a whole, the area where historically defaults have been highest have tended to be in the oil and gas and natural resource sectors.

Mawby says: “If you remember, Gordon Brown once said he had abolished ‘boom and bust’ and conquered the business cycle. He got pilloried for it, but I have some sympathy with his view. Counter cyclical monetary policy has effectively abolished those cycles and replaced them with more volatility.

“It has created a lot of zombie companies, but created a massive debt pile. The credit quality has probably has gone down, and if monetary policy does normalise, they are going to hike into the worst recession since the global financial crisis. That is why we favour the higher quality end of the market.”

Some of the areas of the bond market which are supposed to be safer havens have suffered this year

Mawby says he is of the view that higher interest rates and other policies will soon see the rate of inflation and economic growth decline, and as a result “is starting to think about” buying longer duration assets, which would be typically viewed as the opposite end of the bond market to where high-yield bonds are.

Flavio Carpenzano, fixed income director at Capital Group, says that despite the economic sensitivity of high-yield bonds, they have performed strongly this year because their short duration to maturity, as investors were more focused on inflation worries than growth worries.

But adds he does not believe that growing fears around recession will have a profound impact on high-yield bonds, as the chances of recession in the US are, in his view, quite low, and the high-yield bond market has got more quality in it now than in the past.

Lind says such businesses now make up a smaller part of the high-yield market than ever before, arguably increasing its quality, while the present very high levels of commodity prices mean oil and gas companies are more likely to be able to generate the cash to pay their debts.

High-yield bonds are traditionally more correlated with equities than any other part of the fixed income market, but with the historic inverse correlations between bonds and equities having broken down, investors may not view this in the negative light as in the past.

david.thorpe@ft.com

Chris J. Ratcliffe/Bloomberg

Chris J. Ratcliffe/Bloomberg

AP Photo/Frank Augstein

AP Photo/Frank Augstein

Unsplash/Tim Evans

Unsplash/Tim Evans

House view: The case for high yield

High-yield bonds have traditionally been viewed as one of the riskiest areas of the fixed income markets as they carry a higher risk of default. But there is a strong case to be argued that investors are being compensated richly for this risk today and that they offer effective mitigation against greater threats to portfolios: rising inflation and interest rates.

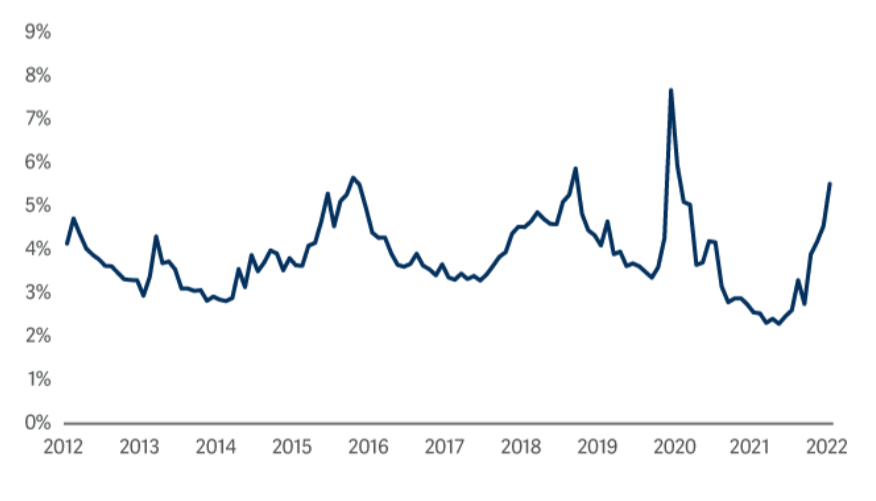

High-yield bonds have, like the rest of the fixed income universe, been materially repriced over the past six months. For example, BB-rated bonds in the US dollar market with a one to five-year maturity yielded 2.5 per cent in October 2021. Today that yield has more than doubled, to 6.1 per cent.

As the chart below shows, this is towards the high end of the range of yields this part of the market has offered over the past decade. The only time it has been materially higher was in the depths of the panicked sell-off prompted by the start of the pandemic.

Yields on 1-5 Year BB-rated bonds in the US dollar market maturing within the next five years are currently towards the top of the range seen over the past decade

Source: Bloomberg

Has the risk of default risen materially in this time? Certainly some areas of the economy are suffering. But interest rates are being raised to control inflation, which is usually a sign of an economy growing too quickly.

In the words of William McChesney Martin, a former Federal Reserve chair, central bankers are “in the position of the chaperone who has ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up”.

A fast-growing economy means companies’ earnings are increasing, supporting their ability to make debt repayments.

The median level of fundamental credit losses for BB-rated bonds going back to 1983 has been 0.3 per cent. This implies a very healthy buffer over likely credit losses of around 5 per cent for the BB-rated part of the market. And it means that interest rate risk accounts for just a small portion of the return.

Consequently, rising interest rates are less concerning in this part of the market because increases have a disproportionately minor effect.

And low sensitivity to interest rates

There is another benefit from exposure to high yield – this is also a part of the market which tends to have low levels of duration.

Duration is the part of fixed income that tends to get hurt in central bank hiking cycles. So while government and investment-grade bonds (which tend to have a lot of duration risk, and not so much credit risk) suffer in hiking cycles as yields rise, high yield tends to perform well.

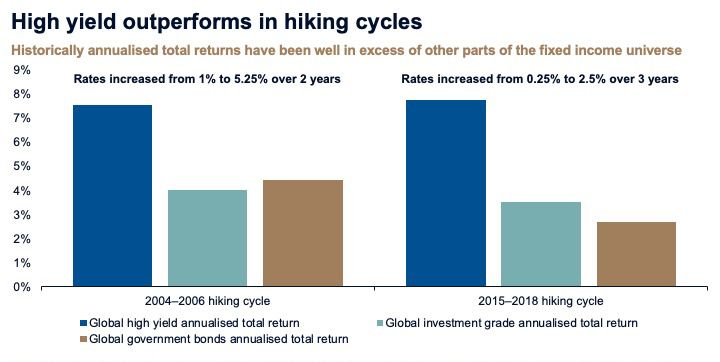

Indeed, over the last two Fed hiking cycles high yield has significantly outperformed wider fixed income and delivered high single-digit percentage annualised returns (see chart below).

Source: Bloomberg. ICE Bofa as at April 14 2021. The 2004-08 hiking cycle data is from June 28 2004 to June 29 2006 and the 2015-18 hiking cycle data is from December 14 2015 to December 19 2018.

As a rough rule of thumb, a 1 per cent rise in yield in a long duration asset will result in a 1 per cent fall in the value of the asset multiplied by its duration. So a 1 per cent rise in the yields of 10-year Treasuries can be expected to lead to an approximate 10 per cent fall in their price.

The average duration of high-yield bonds is four years. And in the ICE BofA 1-5 Year BB Cash Pay High Yield Index, it is just 2.6 years. That means their yields would need to widen to almost 9 per cent over a 12-month period for an exposure to them to generate losses.

Less reward for holding longer duration assets

Normally, longer duration assets compensate for the risk you take that interest rates will rise during the term of the loan. Expressed on a chart, where the vertical axis measures yields and the horizontal axis time, you would see an upward rising curve for bond yields. Today that curve has flattened.

As the next chart demonstrates, the additional yield you would currently receive in exchange for holding longer maturity high-yield bonds is well below the average over the past decade.

Moving from holding one to five-year BB-rated credit in US dollar market to five to 10-year credit would result in a pick-up in yield of just 0.3 per cent. If you are not being rewarded for long duration, that means you are not being penalised for buying short-duration assets.

The spread in yields between short and long-maturity bonds

in the US high-yield market is unusually low relative to the past decade

Source: Bloomberg

A flat yield curve presents opportunities

Due to the current flatness of yield curves (in both the government bond and credit markets), we believe we can deliver attractive ‘carry’ without subjecting investors to the higher duration and volatility that would result if we were to buy longer dated bonds.

Shorter duration has another benefit: we do not have to look so far ahead. We can have greater confidence in the projected cash flows of a business when assessing credit risk over the next two to three years than we can for the eight to 10-year views required in other parts of the market.

Active management

So far, we have looked at the difference between today’s yields and historic credit risk; we have identified the fact that high-yield credit tends to come with shorter duration; and we have looked at the shape of yield curves to see that the opportunity cost of sitting in the short-duration arena is low.

The final area to examine is the benefit of active management. An active manager can focus on the higher-quality areas of the high-yield market. As we said earlier, the historic default rate for BB-rated bonds is 0.3 per cent. In contrast, CCC-rated bonds, which are also included within the high-yield space, have seen average annual credit losses of 8.1 per cent.

An active manager can also reduce duration, through credit selection. And they can reduce risk further by focusing on areas of the market less vulnerable to rising inflation and interest rates.

We look for robust business models

Like equity managers, we look for companies that have strong pricing power and which are better positioned to deal with rising costs – including the cost of debt, which becomes important as borrowing comes up for refinancing. We avoid companies with business models predicated on high levels of leverage. We can also monitor valuations.

And we manage risk

We reduced risk in the fund last summer. Valuations reflected an optimistic news flow – there was little headroom for further upside and a lot more potential for a downturn. We wanted some protection from this.

Today valuations are much more supportive, pricing in more aggressive moves from the central banks than we think likely. We feel there is runway for growth to be reduced materially without plunging us into recession.

Across the fixed income team, within our strategic and target return funds, we are increasing exposure to high yield.

David Ennett is co-manager of the Artemis High Income Fund and the Artemis Funds (Lux) Global High Yield Bond Fund